14 Glaciers

KEY CONCEPTS

At the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

-

- Differentiate the different types of glaciers and contrast them with sea icebergs

- Describe how glaciers form, move, and create landforms

- Describe glacial budget; describe the zones of accumulation, equilibrium, and melting

- Identify glacial erosional and depositional landforms and interpret their origin; describe glacial lakes

- Describe the history and causes of past glaciations and their relationship to climate, sea-level changes, and isostatic rebound

The Earth’s cryosphere, or ice, has a unique set of erosional and depositional features compared to its hydrosphere, or liquid water. This ice exists primarily in two forms, glaciers and icebergs. Glaciers are large accumulations of ice that exist year-round on the land surface. In contrast, masses ice floating on the ocean are icebergs, although they may have had their origin in glaciers.

Glaciers cover about 10% of the Earth’s surface and are powerful erosional agents that sculpt the planet’s surface. These enormous masses of ice usually form in mountainous areas that experience cold temperatures and high precipitation. Glaciers also occur in low lying areas such as Greenland and Antarctica that remain extremely cold year-round.

14.1 Glacier Formation

Glaciers form when repeated annual snowfall accumulates deep layers of snow that are not completely melted in the summer. Thus there is an accumulation of snow that builds up into deep layers. Perennial snow is a snow accumulation that lasts all year. A thin accumulation of perennial snow is a snow field. Over repeated seasons of perennial snow, the snow settles, compacts, and bonds with underlying layers. The amount of void space between the snow grains diminishes. As the old snow gets buried by more new snow, the older snow layers compact into firn, or névé, a granular mass of ice crystals. As the firn continues to be buried, compressed, and recrystallizes, the void spaces become smaller and the ice becomes less porous, eventually turning into glacier ice. Solid glacial ice still retains a fair amount of void space and that traps air. These small air pockets provide records of the past atmosphere composition.

There are three general types of glaciers: alpine or valley glaciers, ice sheets, and ice caps. Most alpine glaciers are located in the world’s major mountain ranges such as the Andes, Rockies, Alps, and Himalayas, usually occupying long, narrow valleys. Alpine glaciers may also form at lower elevations in areas that receive high annual precipitation such as the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state.

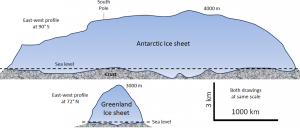

Ice sheets, also called continental glaciers, form across millions of square kilometers of land and are thousands of meters thick. Earth’s largest ice sheets are located on Greenland and Antarctica. The Greenland Ice Sheet is the largest ice mass in the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive surface area of over 2 million sq km (1,242,700 sq mi) and an average thickness of up to 1500 meters (5,000 ft, almost a mile) [1].

The Antarctic Ice Sheet is even larger and covers almost the entire continent. The thickest parts of the Antarctic ice sheet are over 4,000 meters thick (>13,000 ft or 2.5 mi). Its weight depresses the Antarctic bedrock to below sea level in many places. The cross-sectional diagram comparing the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets illustrates the size difference between the two.

Ice cap glaciers are smaller versions of ice sheets that cover less than 50,000 km2 and usually occupy higher elevations and may cover tops of mountains. There are several ice caps on Iceland. A small ice cap called Snow Dome is near Mt. Olympus on the Olympic Peninsula in the state of Washington.

|

|

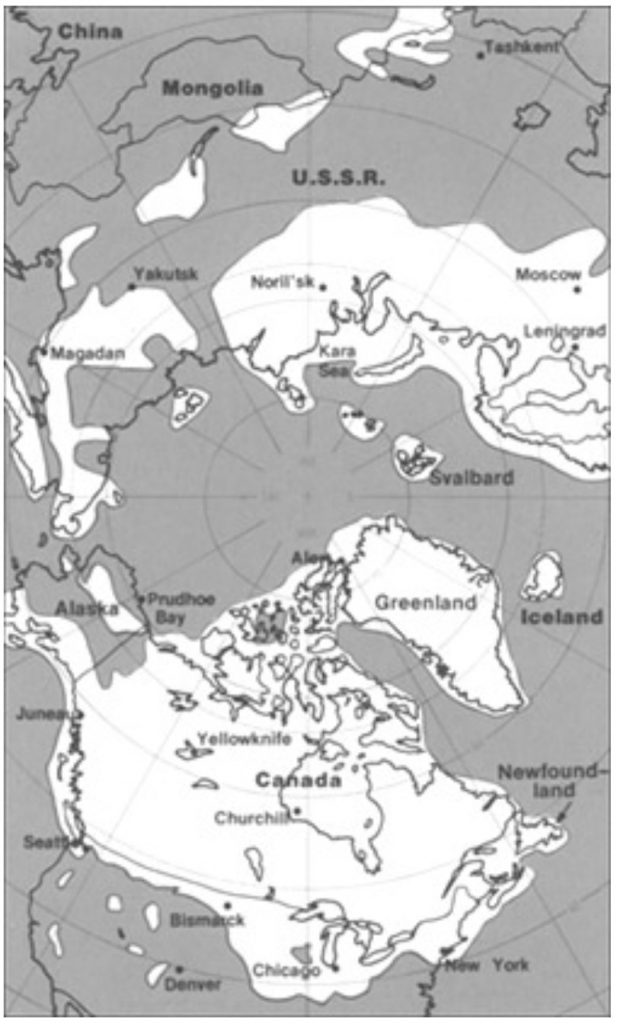

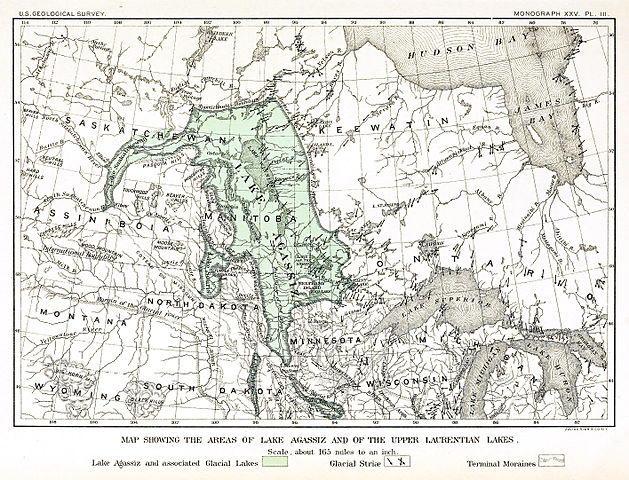

The figure shows the size of the ancient Laurentide Ice Sheet in the Northern Hemisphere. This ice sheet was present during the last glacial maximum event, also known as the last Ice Age.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

14. 2 Glacier Movement

|

|

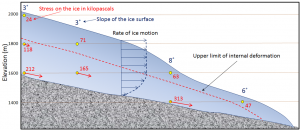

As the ice accumulates, it begins to flow downward under its own weight. In 1948, glaciologists installed hollow vertical rods in into the Jungfraufirn Glacier in the Swiss Alps to measure changes in its movement over two years. This study showed that the ice at the surface was fairly rigid and ice within the glacier was actually flowing downhill. The cross-sectional diagram of an alpine (valley) glacier shows that the rate of ice movement is slow near the bottom, and fastest in the middle with the top ice being carried along on the ice below.

One of the unique properties of ice is that it melts under pressure. About half of the overall glacial movement was from sliding on a film of meltwater along the bedrock surface and half from internal flow. Ice near the surface of the glacier is rigid and brittle to a depth of about 50 m (165 ft). In this brittle zone, large ice cracks called crevasses form on the glacier’s moving surface. These crevasses can be covered and hidden by a snow bridge and are a hazard for glacier travelers.

Below the brittle zone, the pressure typically exceeds 100 kilopascals (kPa), which is –approximately 100,000 times atmospheric pressure. Under this applied force, the ice no longer breaks, but rather it bends or flows in a zone called the plastic zone. This plastic zone represents the great majority of glacier ice. The plastic zone contains a fair amount of sediment of various grades from boulders to silt and clay. As the bottom of the glacier slides and grinds across the bedrock surface, these sediments act as grinding agents and create a zone of significant erosion.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

14.3 Glacial Budget

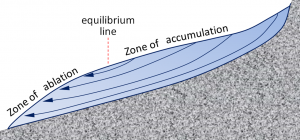

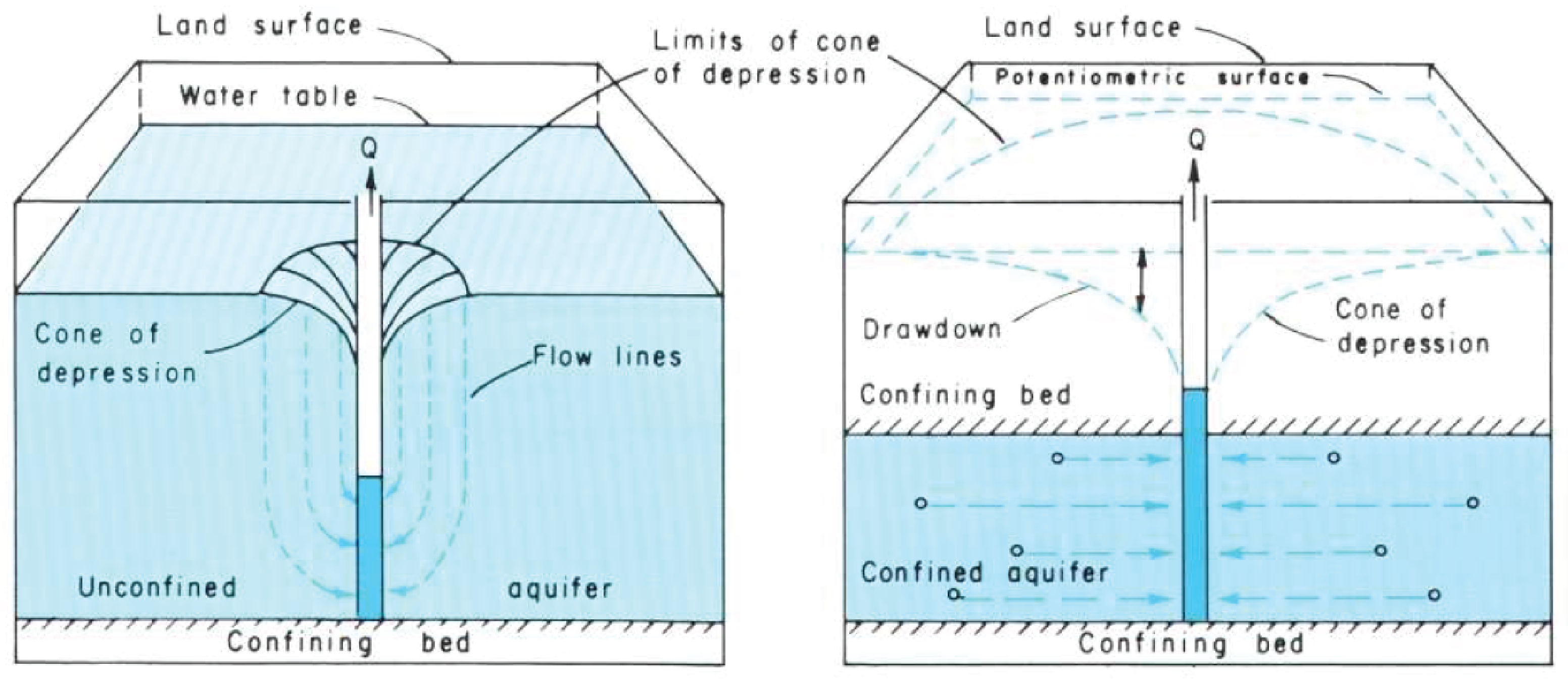

A glacial budget is like a bank account, with the ice being the existing balance. If there is more income (snow accumulating in winter) than expense (snow and ice melting in summer), then the glacial budget shows growth. A positive or negative balance of ice in the overall glacial budget determines whether a glacier advances or retreats, respectively. The area where the ice balance is growing is called the zone of accumulation. The area where ice balance is shrinking is called the zone of ablation.

The diagram shows these two zones and the equilibrium line. In the zone of accumulation, the snow accumulation rate exceeds the snow melting rate and the ice surface is always covered with snow. The equilibrium line, also called the snowline or firnline, marks the boundary between the zones of accumulation and ablation. Below the equilibrium line in the zone of ablation, the melting rate exceeds snow accumulation leaving the bare ice surface exposed. The position of the firnline changes during the season and from year to year as a reflection of a positive or negative ice balance in the glacial budget. Of the two variables affecting a glacier‘s budget, winter accumulation and summer melt, summer melt matters most to a glacier’s budget. Cool summers promote glacial advance and warm summers promote glacial retreat .

If a handful of warmer summers promote glacial retreat, then global climate warming over decades and centuries will accelerate glacial melting and retreat even faster. Global warming due to human burning of fossil fuels is causing the ice sheets to lose in years, an amount of mass that would normally take centuries. Current glacial melting is contributing to rising sea–levels faster than expected based on previous history.

As the Antarctica and Greenland ice sheets melt during global warming, they become thinner or deflate. The edges of the ice sheets break off and fall into the ocean, a process called calving, becoming floating icebergs. A fjord is a steep-walled valley flooded with sea water. The narrow shape of a fjord has been carved out by a glacier during a cooler climate period. During a warming trend, glacial meltwater may raise the sea level in fjords and flood formerly dry valleys [8, 9]. Glacial retreat and deflation are well illustrated in the 2009 TED Talk by James Balog.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

14.4 Glacial Landforms

Both alpine and continental glaciers create two categories of landforms: erosional and depositional. Erosional landforms are formed by the removal of material. Depositional landforms are formed by the addition of material. Because glaciers were first studied by 18th and 19th century geologists in Europe, the terminology applied to glaciers and glacial features contains many terms derived from European languages.

14.4.1 Erosional Glacial Landforms

Erosional landforms are created when moving masses of glacial ice slide and grind over bedrock. Glacial ice contains large amounts of poorly sorted sand, gravel, and boulders that have been plucked and pried from the bedrock. As the glaciers slide across the bedrock, they grind these sediments into a fine powder called rock flour. Rock flour acts as fine grit that polishes the surface of the bedrock to a smooth finish called glacial polish. Larger rock fragments scrape over the surface creating elongated grooves called glacial striations.

|

|

Alpine glaciers produce a variety of unique erosional landforms, such as U-shaped valleys, arêtes, cirques, tarns, horns, cols, hanging valleys, and truncated spurs. In contrast, stream-carved canyons have a V-shaped profile when viewed in cross-section. Glacial erosion transforms a former V-shaped stream valley into a U-shaped one. Glaciers are typically wider than streams of similar length, and since glaciers tend to erode both at their bases and their sides, they erode V-shaped valleys into relatively flat-bottomed broad valleys with steep sides and a distinctive “U” shape. As seen in the images, Little Cottonwood Canyon near Salt Lake City, Utah was occupied by an Ice Age glacier that extended down to the mouth of the canyon and into Lake Bonneville. Today, that U-shaped valley hosts many erosional landforms, including polished and striated rock surfaces. In contrast, Big Cottonwood Canyon to the north of Little Cottonwood Canyon has retained the V-shape in its lower portion, indicating that its glacier did not extend clear to its mouth, but was confined to its upper portion.

|

|

![By Cecilia Bernal (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://integrations.pressbooks.network/app/uploads/sites/516/2022/05/Glacier_Valley_formation-_Formacion_Valle_glaciar-300x200.gif)

When glaciers carve two U-shaped valleys adjacent to each other, the ridge between them tends to be sharpened into a sawtooth feature called an arête. At the head of a glacially carved valley is a bowl-shaped feature called a cirque. The cirque represents where the head of the glacier eroded the mountain by plucking rock away from it and the weight of the thick ice eroded out a bowl. After the glacier is gone, the bowl at the bottom of the cirque often fills with precipitation and is occupied by a lake, called a tarn. When three or more mountain glaciers erode headward at their cirques, they produce horns, steep-sided, spire-shaped mountains. Low points along arêtes or between horns are mountain passes termed cols. Where a smaller tributary glacier flows into a larger trunk glacier, the smaller glacier cuts down less. Once the ice has gone, the tributary valley is left as a hanging valley, sometimes with a waterfall plunging into the main valley. As the trunk glacier straightens and widens a V-shaped valley and erodes the ends of side ridges, a steep triangle-shaped cliff is formed called a truncated spur.

14.4.2 Depositional Glacial Landforms

Depositional landforms and materials are produced from deposits left behind by a retreating glacier. All glacial deposits are called drift. These include till, tillites, diamictites, terminal moraines, recessional moraines, lateral moraines, medial moraines, ground moraines, silt, outwash plains, glacial erratics, kettles, kettle lakes, crevasses, eskers, kames, and drumlins.

Glacial ice carries a lot of sediment, which when deposited by a melting glacier is called till. Till is poorly sorted with grain sizes ranging from clay and silt to pebbles and boulders. These clasts may be striated. Many depositional landforms are composed of till. The term tillite refers to lithified rock having glacial origins. Diamictite refers to a lithified rock that contains a wide range of clast sizes; this includes glacial till but is a more objective and descriptive term for any rock with a wide range of clast sizes.

Moraines are mounded deposits consisting of glacial till carried in the glacial ice and rock fragments dislodged by mass wasting from the U-shaped valley walls. The glacier acts like a conveyor belt, carrying and depositing sediment at the end of and along the sides of the ice flow. Because the ice in the glacier is always flowing downslope, all glaciers have moraines build up at their terminus, even those not advancing.

Moraines are classified by their location with respect to the glacier. A terminal moraine is a ridge of till located at the end or terminus of the glacier. Recessional moraines are left as glaciers retreat and there are pauses in the retreat. Lateral moraines accumulate along the sides of the glacier from material mass wasted from the valley walls. When two tributary glaciers merge, the two lateral moraines combine to form a medial moraine running down the center of the combined glacier. Ground moraine is a veneer of till left on the land as the glacier melts.

In addition to moraines, glaciers leave behind other depositional landforms. Silt, sand, and gravel produced by the intense grinding process are carried by streams of water and deposited in front of the glacier in an area called the outwash plain. Retreating glaciers may leave behind large boulders that don’t match the local bedrock. These are called glacial erratics. When continental glaciers retreat, they can leave behind large blocks of ice within the till. These ice blocks melt and create a depression in the till called a kettle. If the depression later fills with water, it is called a kettle lake.

If meltwater flowing over the ice surface descends into crevasses in the ice, it may find a channel and continue to flow in sinuous channels within or at the base of the glacier. Within or under continental glaciers, these streams carry sediments. When the ice recedes, the accumulated sediment is deposited as a long sinuous ridge known as an esker. Meltwater descending down through the ice or over the margins of the ice may deposit mounds of till in hills called kames.

Drumlins are common in continental glacial areas of Germany, New York, and Wisconsin, where they typically are found in fields with great numbers. A drumlin is an elongated asymmetrical teardrop-shaped hill reflecting ice movement with its steepest side pointing upstream to the flow of ice and its streamlined or low–angled side pointing downstream in the direction of ice movement.

Glacial scientists debate the origins of drumlins. A leading idea is that drumlins are created from accumulated till being compressed and sculpted under a glacier that retreated then advanced again over its own ground moraine. Another idea is that meltwater catastrophically flooded under the glacier and carved the till into these streamlined mounds. Still another proposes that the weight of the overlying ice statically deformed the underlying till[12, 13].

14.4.3 Glacial Lakes

Glacial lakes are commonly found in alpine environments. A lake confined within a glacial cirque is called a tarn. A tarn forms when the depression in the cirque fills with precipitation after the ice is gone. Examples of tarns include Silver Lake near Brighton Ski resort in Big Cottonwood Canyon, Utah and Avalanche Lake in Glacier National Park, Montana.

When recessional moraines create a series of isolated basins in a glaciated valley, the resulting chain of lakes is called paternoster lakes.

Lakes filled by glacial meltwater often looks milky due to finely ground material called rock flour suspended in the water.

Long, glacially carved depressions filled with water are known as finger lakes. Proglacial lakes form along the edges of all the largest continental ice sheets, such as Antarctica and Greenland. The crust is depressed isostatically by the overlying ice sheet and these basins fill with glacial meltwater. Many such lakes, some of them huge, existed at various times along the southern edge of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Lake Agassiz, Manitoba, Canada, is a classic example of a proglacial lake. Lake Winnipeg serves as the remnant of a much larger proglacial lake.

Other proglacial lakes were formed when glaciers dammed rivers and flooded the river valley. A classic example is Lake Missoula, which formed when a lobe of the Laurentide ice sheet blocked the Clark Fork River about 18,000 years ago. Over about 2000 years the ice dam holding back Lake Missoula failed several times. During each breach, the lake emptied across parts of eastern Washington, Oregon, and Idaho into the Columbia River Valley and eventually the Pacific Ocean. After each breach, the dam reformed and the lake refilled. Each breach produced a catastrophic flood over a few days. Scientists estimate that this cycle of ice dam, proglacial lake, and torrential massive flooding happened at least 25 times over a span of 20 centuries. The rate of each outflow is believed to have equaled the combined discharge of all of Earth’s current rivers combined.

The landscape produced by these massive floods is preserved in the Channeled Scablands of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

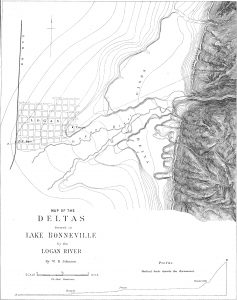

Pluvial lakes form in humid environments that experience low temperatures and high precipitation. During the last glaciation, most of the western United States’ climate was cooler and more humid than today. Under these low-evaporation conditions, many large lakes, called pluvial lakes, formed in the basins of the Basin and Range Province. Two of the largest were Lake Bonneville and Lake Lahontan. Lake Lahontan was in northwestern Nevada. The figure illustrates the tremendous size of Lake Bonneville, which occupied much of western Utah and into eastern Nevada. The lake level fluctuated greatly over the centuries leaving several pronounced old shorelines marked by wave-cut terraces. These old shorelines can be seen on mountain slopes throughout the western portion of Utah, including the Salt Lake Valley, indicating that the now heavily urbanized valley was once filled with hundreds of feet of water. Lake Bonneville‘s level peaked around 18,000 years ago when a breach occurred at Red Rock Pass in Idaho and water spilled into the Snake River. The flooding rapidly lowered the lake level and scoured the Idaho landscape across the Pocatello Valley, the Snake River Plain, and Twin Falls. The floodwaters ultimately flowed into the Columbia River across part of the scablands area at an incredible discharge rate of about 4,750 cu km/sec (1,140 cu mi/sec). For comparison, this discharge rate would drain the volume of Lake Michigan completely dry within a few days.

The five Great Lakes in North America’s upper Midwest are proglacial lakes that originated during the last ice age. The lake basins were originally carved by the encroaching continental ice sheet. The basins were later exposed as the ice retreated about 14,000 years ago and filled by precipitation.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

14.5 Ice Age Glaciations

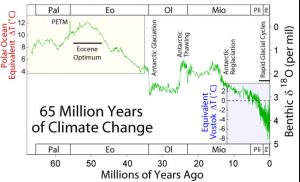

A glaciation or ice age) occurs when the Earth’s climate becomes cold enough that continental ice sheets expand, covering large areas of land. Four major, well–documented glaciations have occurred in Earth’s history: one during the Archean-early Proterozoic Eon, ~2.5 billion years ago; another in late Proterozoic Eon, ~700 million years ago; another in the Pennsylvanian, 323 to 300 million years ago, and most recently during the Pliocene-Pleistocene epochs starting 2.5 million years ago (Chapter 8). Some scientists also recognize a minor glaciation around 440 million years ago in Africa.

The best–studied glaciation is, of course, the most recent. This infographic illustrates the glacial and climate changes over the last 20,000 years, ending with those caused by human actions since the Industrial Revolution. The Pliocene-Pleistocene glaciation was a series of several glacial cycles, possibly 18 in total. Antarctic ice–core records exhibit especially strong evidence for eight glacial advances occurring within the last 420,000 years [16]. The last of these is known in popular media as “The Ice Age,” but geologists refer to it as the Last Glacial Maximum. The glacial advance reached its maximum between 26,500 and 19,000 years ago [10, 17].

14.5.1 Causes of Glaciations

Glaciations occur due to both long-term and short–term factors. In the geologic sense, long-term means a scale of tens to hundreds of millions of years and short-term means a scale of hundreds to thousands of years.

Long-term causes include plate tectonics breaking up the supercontinents (see Wilson Cycle, Chapter 2), moving land masses to high latitudes near the north or south poles, and changing ocean circulation. For example, the closing of the Panama Strait and isolation of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans may have triggered a change in precipitation cycles, which combined with a cooling climate to help expand the ice sheets.

Short-term causes of glacial fluctuations are attributed to the cycles in the Earth’s rotational–axis and to variations in the earth’s orbit around the Sun which affect the distance between Earth and the Sun. Called Milankovitch Cycles, these cycles affect the amount of incoming solar radiation, causing short-term cycles of warming and cooling.

During the Cenozoic Era, carbon dioxide levels steadily decreased from a maximum in the Paleocene, causing the climate to gradually cool. By the Pliocene, ice sheets began to form. The effects of the Milankovitch Cycles created short-term cycles of warming and cooling within the larger glaciation event.

Milankovitch Cycles are three orbital changes named after the Serbian astronomer Milutan Milankovitch. The three orbital changes are called precession, obliquity, and eccentricity. Precession is the wobbling of Earth’s axis with a period of about 21,000 years; obliquity is changes in the angle of Earth’s axis with a period of about 41,000 years; and eccentricity is variations in the Earth’s orbit around the sun leading to changes in distance from the sun with a period of 93,000 years [19]. These orbital changes created a 41,000–year-long glacial–interglacial Milankovitch Cycle from 2.5 to 1.0 million years ago, followed by another longer cycle of about 100,000 years from 1.0 million years ago to today (see Milankovitch Cycles).

Watch the video to see summaries of the ice ages, including their characteristics and causes.

14.5.2 Sea-Level Change and Isostatic Rebound

When glaciers melt and retreat, two things happen: water runs off into the ocean causing sea levels to rise worldwide, and the land, released from its heavy covering of ice, rises due to isostatic rebound. Since the Last Glacial Maximum about 19,000 years ago, sea–level has risen about 125 m (400 ft). A global change in sea level is called eustatic sea-level change. During a warming trend, sea–level rises due to more water being added to the ocean and also thermal expansion of sea water. About half of the Earth’s eustatic sea-level rise during the last century has been the result of glaciers melting and about half due to thermal expansion [21, 22]. Thermal expansion describes how a solid, liquid, or gas expands in volume with an increase in temperature. This 30 second video demonstrates thermal expansion with the classic brass ball and ring experiment.

Relative sea-level change includes vertical movement of both eustatic sea-level and continents on tectonic plates. In other words, sea-level change is measured relative to land elevation. For example, if the land rises a lot and sea-level rises only a little, then the relative sea-level would appear to drop.

Continents sitting on the lithosphere can move vertically upward as a result of two main processes, tectonic uplift and isostatic rebound. Tectonic uplift occurs when tectonic plates collide (see Chapter 2). Isostatic rebound describes the upward movement of lithospheric crust sitting on top of the asthenospheric layer below it. Continental crust bearing the weight of continental ice sinks into the asthenosphere displacing it. After the ice sheet melts away, the asthenosphere flows back in and continental crust floats back upward. Erosion can also create isostatic rebound by removing large masses like mountains and transporting the sediment away (think of the Mesozoic removal of the Alleghanian Mountains and the uplift of the Appalachian plateau; Chapter 8), albeit this process occurs more slowly than relatively rapid glacier melting.

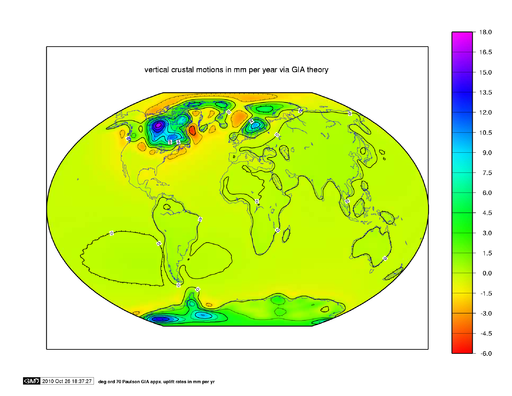

The isostatic–rebound map below shows rates of vertical crustal movement worldwide. The highest rebound rate is indicated by the blue-to-purple zones (top end of the scale). The orange-to-red zones (bottom end of the scale) surrounding the high-rebound zones indicate isostatic lowering as adjustments in displaced subcrustal material have taken place.

Most glacial isostatic rebound is occurring where continental ice sheets rapidly melted about 19,000 years ago, such as in Canada and Scandinavia. Its effects can be seen wherever Ice Age ice or water bodies are or were present on continental surfaces and in terraces on river floodplains that cross these areas. Isostatic rebound occurred in Utah when the water from Lake Bonneville drained away [23]. North America’s Great Lakes also exhibit emergent coastline features caused by isostatic rebound since the continental ice sheet retreated.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

Summary

Glaciers form when average annual snowfall exceeds melting and snow compresses into glacial ice. There are three types of glaciers, alpine or valley glaciers that occupy valleys, ice sheets that cover continental areas, and ice caps that cover smaller areas usually at higher elevations. As the ice accumulates, it begins to flow downslope and outward under its own weight. Glacial ice is divided into two zones, the upper rigid or brittle zone where the ice cracks into crevasses and the lower plastic zone where under the pressure of overlying ice, the ice bends and flows exhibiting ductile behavior. Rock material that falls onto the ice by mass wasting or is plucked and carried by the ice is called moraine and acts as grinding agents against the bedrock creating significant erosion.

Glaciers have a budget of income and expense. The zone of income for the glacier is called the Zone of Accumulation, where snow is converted into firn then ice by compression and recrystallization, and the zone of expense called the Zone of Ablation, where ice melts or sublimes away. The line separating these two zones latest in the year is the Equilibrium or Firn Line and can be seen on the glacier separating bare ice from snow covered ice. If the glacial budget is balanced, even though the ice continues to flow downslope, the end or terminus of the glacier remains in a stable position. If income is greater than expense, the position of the terminus moves downslope. If expense is greater than income, a circumstance now affecting glaciers and ice sheets worldwide due to global warming, the terminus recedes. If this situation continues, the glaciers will disappear. An average of cooler summers affects the stability or growth of glaciers more than higher snowfall. As the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets flow seaward, the edges calve off forming icebergs.

Glaciers create two kinds of landforms, erosional and depositional. Alpine glaciers carve U-shaped valleys and moraine carried in the ice polishes and grooves or striates the bedrock. Other landscape features produced by erosion include horns, arête ridges, cirques, hanging valleys, cols, and truncated spurs. Cirques may contain eroded basins that are occupied by post glacial lakes called tarns. Depositional features result from deposits left by retreating ice called drift. These include till, and moraine deposits (terminal, recessional, lateral, medial, and ground), eskers, kames, kettles and kettle lakes, erratics, and drumlins. A series of recessional moraines in glaciated valleys may create basins that are later filled with water to become paternoster lakes. Glacial meltwater carries fine grained sediment onto the outwash plain. Lakes containing glacial meltwater are milky in color from suspended finely ground rock flour. Ice Age climate was more humid and precipitation that did not become glacier ice filled regional depressions to become pluvial lakes. Examples of pluvial lakes include Lake Missoula dammed behind an ice sheet lobe and Lake Bonneville in Utah whose shoreline remnants can be seen on mountainsides. Repeated breaching of the ice lobe allowed Lake Missoula to rapidly drain causing massive floods that scoured the Channeled Scablands of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this Chapter.

References

- Allen, P.A., and Etienne, J.L., 2008, Sedimentary challenge to Snowball Earth: Nat. Geosci., v. 1, no. 12, p. 817–825.

- Berner, R.A., 1998, The carbon cycle and carbon dioxide over Phanerozoic time: the role of land plants: Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., v. 353, no. 1365, p. 75–82.

- Cunningham, W.L., Leventer, A., Andrews, J.T., Jennings, A.E., and Licht, K.J., 1999, Late Pleistocene–Holocene marine conditions in the Ross Sea, Antarctica: evidence from the diatom record: The Holocene, v. 9, no. 2, p. 129–139.

- Deynoux, M., Miller, J.M.G., and Domack, E.W., 2004, Earth’s Glacial Record: World and Regional Geology, Cambridge University Press, World and Regional Geology.

- Earle, S., 2015, Physical geology OER textbook: BC Campus OpenEd.

- Eyles, N., and Januszczak, N., 2004, “Zipper-rift”: a tectonic model for Neoproterozoic glaciations during the breakup of Rodinia after 750 Ma: Earth-Sci. Rev.

- Francey, R.J., Allison, C.E., Etheridge, D.M., Trudinger, C.M., and others, 1999, A 1000‐year high precision record of δ13C in atmospheric CO2: Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol.

- Gutro, R., 2005, NASA – What’s the Difference Between Weather and Climate? Online, http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/noaa-n/climate/climate_weather.html, accessed September 2016.

- Hoffman, P.F., Kaufman, A.J., Halverson, G.P., and Schrag, D.P., 1998, A neoproterozoic snowball earth: Science, v. 281, no. 5381, p. 1342–1346.

- Kopp, R.E., Kirschvink, J.L., Hilburn, I.A., and Nash, C.Z., 2005, The Paleoproterozoic snowball Earth: a climate disaster triggered by the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., v. 102, no. 32, p. 11131–11136.

- Lean, J., Beer, J., and Bradley, R., 1995, Reconstruction of solar irradiance since 1610: Implications for climate cbange: Geophys. Res. Lett., v. 22, no. 23, p. 3195–3198.

- Levitus, S., Antonov, J.I., Wang, J., Delworth, T.L., Dixon, K.W., and Broccoli, A.J., 2001, Anthropogenic warming of Earth’s climate system: Science, v. 292, no. 5515, p. 267–270.

- Lindsey, R., 2009, Climate and Earth’s Energy Budget : Feature Articles: Online, http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov, accessed September 2016.

- North Carolina State University, 2013a, Composition of the Atmosphere:

- North Carolina State University, 2013b, Composition of the Atmosphere: Online, http://climate.ncsu.edu/edu/k12/.AtmComposition, accessed September 2016.

- Oreskes, N., 2004, The scientific consensus on climate change: Science, v. 306, no. 5702, p. 1686–1686.

- Pachauri, R.K., Allen, M.R., Barros, V.R., Broome, J., Cramer, W., Christ, R., Church, J.A., Clarke, L., Dahe, Q., Dasgupta, P., Dubash, N.K., Edenhofer, O., Elgizouli, I., Field, C.B., and others, 2014, Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (R. K. Pachauri & L. Meyer, Eds.): Geneva, Switzerland, IPCC, 151 p.

- Santer, B.D., Mears, C., Wentz, F.J., Taylor, K.E., Gleckler, P.J., Wigley, T.M.L., Barnett, T.P., Boyle, J.S., Brüggemann, W., Gillett, N.P., Klein, S.A., Meehl, G.A., Nozawa, T., Pierce, D.W., and others, 2007, Identification of human-induced changes in atmospheric moisture content: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., v. 104, no. 39, p. 15248–15253.

- Schopf, J.W., and Klein, C., 1992, Late Proterozoic Low-Latitude Global Glaciation: the Snowball Earth, in Schopf, J.W., and Klein, C., editors, The Proterozoic biosphere : a multidisciplinary study: New York, Cambridge University Press, p. 51–52.

- Webb, T., and Thompson, W., 1986, Is vegetation in equilibrium with climate? How to interpret late-Quaternary pollen data: Vegetatio, v. 67, no. 2, p. 75–91.

- Weissert, H., 2000, Deciphering methane’s fingerprint: Nature, v. 406, no. 6794, p. 356–357.

- Whitlock, C., and Bartlein, P.J., 1997, Vegetation and climate change in northwest America during the past 125 kyr: Nature, v. 388, no. 6637, p. 57–61.

- Wolpert, S., 2009, New NASA temperature maps provide a ‘whole new way of seeing the moon’: Online, http://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/new-nasa-temperature-maps-provide-102070, accessed February 2017.

- Zachos, J., Pagani, M., Sloan, L., Thomas, E., and Billups, K., 2001, Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present: Science, v. 292, no. 5517, p. 686–693.

Mention de la source du contenu multimédia

- Grosser_Aletschgletscher_3178

- Greenland

- Greenland_ice_sheet_AMSL_thickness_map

- Steve Earle_antarctic-greenland-2-300×128

- Snow-Dome-ice-cap

- Vatnajokull-ice-cap-in-Iceland

- Maximum-extent-of-Laurentide-ice-sheet

- 14.1 Did I Get It QR Code

- Chevron_Crevasses_00

- Glaciereaston

- Steve Earle_ice flow and stress

- 14.2 Did I Get It QR Code

- ice-flow-2

- Geirangerfjord_(6-2007)

- Time-Lapse Proof of Extreme Ice Loss TED Talk Video QR Code

- 14.3 Did I Get It QR Code

- GlacialPolish

- Glacial_striation_21149

- UshapedValleyUT

- V-shaped Big Cottonwood

- Glacier_Valley_formation-_Formación_Valle_glaciar

- Thornton_Lakes_25929

- Kinnerly_Peak

- Closeup_of_Bridalveil_Fall_seen_from_Tunnel_View_in_Yosemite_NP

- 14.4.1 Erosional Glaciers Interactive Activity QR Code

- Diamictite_Mineral_Fork

- UGA02-0787-n7b

- Drumlins in Germany

- 14.4.2 Depositional Glaciers Interactive Activity QR Code

- Verdi_Leak_in_The_Ruby_Mountains-e1496442171386

- Paternoster lakes

- Satellite photo of Finger Lakes region of New York

- Agassiz

- View of the Channeled Scablands of Eastern Washington

- Lake_bonneville_map.svg_

- The great lakes

- 14.4 Did I Get It QR Code

- CO2 in the Cenozoic

- 14.5.1 Causes of Glaciations Interactive Activity

- Ice Ages & Climate Cycles Youtube QR Code

- Ball and Ring Rate of Expansion and Contraction Youtube QR Code

- Map showing greatest rebound rates in the areas of recent glaciation.

- 14.5 Did I Get It QR Code

- Ch.14 Review QR Code

Component of the gravitational force which pushes material downslope.

A slope, that by natural or human activity, becomes steeper than the angle of repose.

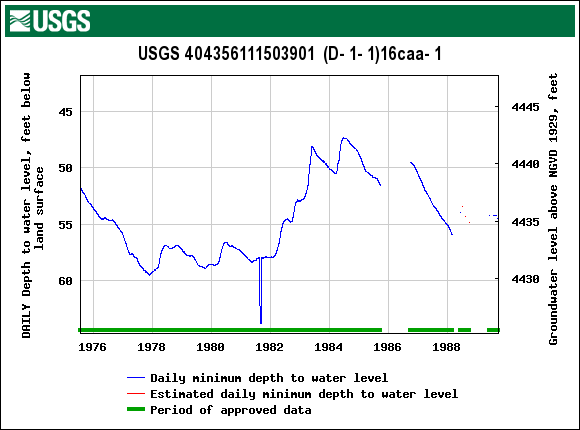

https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/dv/?ts_id=143976&format=img_default&site_no=404356111503901&set_arithscale_y=on&begin_date=19750718&end_date=19890930

Photo credit to Louis J. Maher, Jr.

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

A geologic circumstance (such as a fold, fault, change in lithology, etc.) which allows petroleum resources to collect.

A rock that contains material which can be turned into petroleum resources. Organic-rich muds form good source rocks.

Empty space in a geologic material, either within sediments, or within rocks. Can be filled by air, water, or hydrocarbons.

Rocks which allow petroleum resources to collect or move.

The relationship between shear force and normal force in a block of material on a slope. When shear force is greater than normal force, mass wasting can occur.

Slope angle where shear forces and normal forces are equal.

Component of the gravitational force which holds material on a slope.

Erosional rock face caused by sand abrasion.

Place where oceanic-oceanic subduction causes volcanoes to form on an overriding oceanic plate, making a chain of active volcanoes.

By G. Thomas at English Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

A sedimentary structure that has inclined layers within an overall layer. Forms commonly in dunes, larger in eolian dunes.

An event that causes a landslide event. Water is a common trigger.

Carbonate rock that reacts with hot magmatic fluids, creating concentrated ore deposits, which include copper, iron, zinc, and gold.

Oxidation that occurs in sulfide deposits which can concentrate valuable elements like copper.

Detached, free-falling rocks from very steep slopes.

A landslide that moves a long an internal plane of weakness.

Large and mysterious landslides that travel for long distances.

A rock made of primarily silt.

Plastic moving, fine-grained type of flow.

A mixture of coarse material and water, channeled and flowing downhill rapidly.

Very slow movement of the soil downhill.

A combination of evaporation and transpiration from plants, which is a measure of water entering the atmosphere.

Water that flows over the surface.

Water that works its way down into the subsurface.

Water that is below the surface.

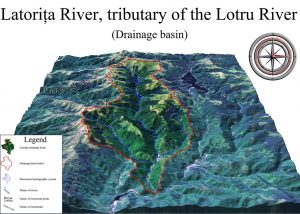

The area within a topographic basin or drainage divide in which water collects.

The measure of degrees north or south from the equator, which has a latitude of 0 degrees. The Earth's north and south poles have latitudes of 90 degrees north and south, respectively.

Loose blocks of rock that fall down from steep surfaces and cover slopes.

Topographic prominence which sheds water into a specific drainage basin.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mississippiriver-new-01.png#metadata

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

Karte: NordNordWest, Lizenz: Creative Commons by-sa-3.0 de [CC BY-SA 3.0 de], via Wikimedia Commons

By Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Source: W.D. Johnson; From Gilbert, 1890, G.K. Lake Bonneville; https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/m1

USGS GK Gilbert 1909 https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/51dc6e2ae4b097e4d3837a63

own work

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

Data which is out of the ordinary and does not fit previous trends.

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/students-3/geography-a-level-2/a-level-geography-fieldwork-investigation/

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

By USGS [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Source: Indiana Department of Natural Resources http://www.in.gov/dnr/water/7258.htm

Dangerous flooding that occurs in arid regions.

The thin, outer layer of the Earth which makes up the rocky bottom of the ocean basins. It is made of rocks similar to basalt, and as it cools, even become more dense than the upper mantle below.

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

Any downhill movement of material, caused by gravity.

Limestone made of primarily fine-grained calcite mud. Microscopic fossils are commonly present.

Discernible layers of rock, typically from a sedimentary rock.

Extremely thin bedding in mudstones, a characteristic of shale.

A rock made primarily of clay.

The process that turns non-desert land into desert.

Rock with abraded surfaces formed in deserts.

Lake that fills a glacial valley.

By Inglesenargentina (talk) (Uploads) (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By Peter Kapitola (Own work) [CC BY-SA 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons

By Krishnavedala (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Heath, R. C. (1983). Basic ground-water hydrology (No. Water-Supply Paper 2220). [Washington, D.C.]; Alexandria, Va.: U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved from http://pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/2220/report.pdf

https://water.usgs.gov/edu/graphics/wcartificialrecharge.gif

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

Source: Paul Inkenbrandt (Knudsen et al. 2014)

Sedimentary rocks made of mineral grains weathered as mechanical detritus of previous rocks, e.g. sand, gravel, etc.

A proven commodity of profitable material that could be mined.

Glaciers that form in cool or mountainous areas.

A body of ice that moves downhill under its own mass.

Thick glaciers that cover continents during ice ages.

QR Code generated with QRCode Monkey. All generated QR Codes are 100% free and can be used for whatever you want. This includes all commercial purposes.

A vast stretch of sand dunes.

Minerals with a luster similar to metal and contain metals, including valuable elements like lead, zinc, copper, tin, etc.

By Zkeizars (Own work) [GFDL or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Movement of regolith along a curved slip plane.

By Matt Affolter

A specific type of sedimentary structure (ripples, plane beds, etc.) linked to a specific flow regime.

by Robert A. Rohde

Lake that forms next to a glacier because of crustal loading.

The study of rock layers and their relationships to each other within a specific area.

By McKay Savage from London, UK [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

11 Water

KEY CONCEPTS

-

Example of a Roman aqueduct in Segovia, Spain. Describe the processes of the water cycle

- Describe drainage basins, watershed protection, and water budget

- Describe reasons for water laws, who controls them, and how water is shared in the western U.S.

- Describe zone of transport, zone of sediment production, zone of deposition, and equilibrium

- Describe stream landforms: channel types, alluvial fans, floodplains, natural levees, deltas, entrenched meanders, and terraces

- Describe the properties required for a good aquifer; define confining layer water table

- Describe three major groups of water contamination and three types of remediation

- Describe karst topography, how it is created, and the landforms that characterize it

All life on Earth requires water. The hydrosphere (Earth’s water) is an important agent of geologic change. Water shapes our planet by depositing minerals, aiding lithification, and altering rocks after they are lithified. Water carried by subducted oceanic plates causes flux melting of upper mantle material. Water is among the volatiles in magma and emerges at the surface as steam in volcanoes.

Humans rely on suitable water sources for consumption, agriculture, power generation, and many other purposes. In pre-industrial civilizations, the powerful controlled water resources [1, 2]. As shown in the figures, two thousand year old Roman aqueducts still grace European, Middle Eastern, and North African skylines. Ancient Mayan architecture depicts water imagery such as frogs, water-lilies, water fowl to illustrate the importance of water in their societies [3]. In the drier lowlands of the Yucatan Peninsula, mask facades of the hooked-nosed rain god, Chac (or Chaac) are prominent on Mayan buildings such as the Kodz Poop (Temple of the Masks, sometimes spelled Coodz Poop) at the ceremonial site of Kabah. To this day government controlled water continues to be an integral part of most modern societies.

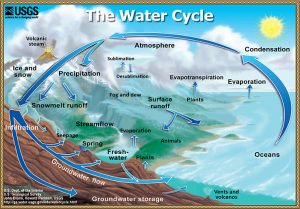

11.1 Water Cycle

The water cycle is the continuous circulation of water in the Earth's atmosphere. During circulation, water changes between solid, liquid, and gas (water vapor) and changes location. The processes involved in the water cycle are evaporation, transpiration, condensation, precipitation, and runoff.

Evaporation is the process by which a liquid is converted to a gas. Water evaporates when solar energy warms the water sufficiently to excite the water molecules to the point of vaporization. Evaporation occurs from oceans, lakes, and streams and the land surface. Plants contribute significant amounts of water vapor as a byproduct of photosynthesis called transpiration that occurs through the minute pores of plant leaves. The term evapotranspiration refers to these two sources of water entering the atmosphere and is commonly used by geologists.

Water vapor is invisible. Condensation is the process of water vapor transitioning to a liquid. Winds carry water vapor in the atmosphere long distances. When water vapor cools or when air masses of different temperatures mix, water vapor may condense back into droplets of liquid water. These water droplets usually form around a microscopic piece of dust or salt called condensation nuclei. These small droplets of liquid water suspended in the atmosphere become visible as in a cloud. Water droplets inside clouds collide and stick together, growing into larger droplets. Once the water droplets become big enough, they fall to Earth as rain, snow, hail, or sleet.

Once precipitation has reached the Earth's surface, it can evaporate or flow as runoff into streams, lakes, and eventually back to the oceans. Water in streams and lakes is called surface water. Or water can also infiltrate into the soil and fill the pore spaces in the rock or sediment underground to become groundwater. Groundwater slowly moves through rock and unconsolidated materials. Some groundwater may reach the surface again, where it discharges as springs, streams, lakes, and the ocean. Also, surface water in streams and lakes can infiltrate again to recharge groundwater. Therefore, the surface water and groundwater systems are connected.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

11.2 Water Basins and Budgets

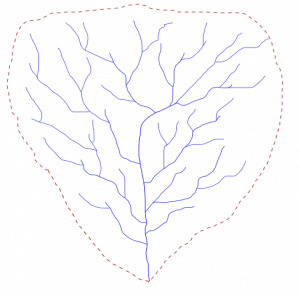

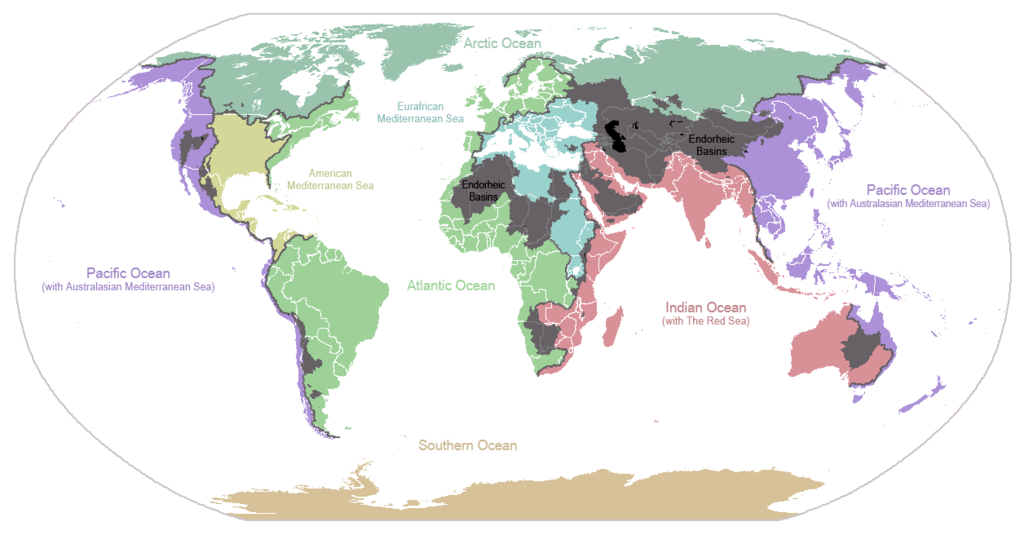

The basic unit of division of the landscape is the drainage basin, also known as a catchment or watershed. It is the area of land that captures precipitation and contributes runoff to a stream or stream segment [4]. Drainage divides are local topographic high points that separate one drainage basin from another [5]. Water that falls on one side of the divide goes to one stream, and water that falls on the other side of the divide goes to a different stream. Each stream, tributary and streamlet has its own drainage basin. In areas with flatter topography, drainage divides are not as easily identified but they still exist [6].

The headwater is where the stream begins. Smaller tributary streams combine downhill to make the larger trunk of the stream. The mouth is where the stream finally reaches its end. The mouth of most streams is at the ocean. However, a rare number of streams do not flow to the ocean, but rather end in a closed basin (or endorheic basin) where the only outlet is evaporation. Most streams in the Great Basin of Western North America end in endorheic basins. For example, in Salt Lake County, Utah, Little Cottonwood Creek and the Jordan River flow into the endorheic Great Salt Lake where the water evaporates.

Perennial streams flow all year round. Perennial streams occur in humid or temperate climates where there is sufficient rainfall and low evaporation rates. Water levels rise and fall with the seasons, depending on the discharge. Ephemeral streams flow only during rain events or the wet season. In arid climates, like Utah, many streams are ephemeral. These streams occur in dry climates with low amounts of rainfall and high evaporation rates. Their channels are often dry washes or arroyos for much of the year and their sudden flow causes flash floods [7].

Along Utah’s Wasatch Front, the urban area extending north to south from Brigham City to Provo, there are several watersheds that are designated as “watershed protection areas” that limit the type of use allowed in those drainages in order to protect culinary water. Dogs and swimming are limited in those watersheds because of the possibility of contamination by harmful bacteria and substances to the drinking supply of Salt Lake City and surrounding municipalities.

Water in the water cycle is very much like money in a personal budget. Income includes precipitation and stream and groundwater inflow. Expenses include groundwater withdrawal, evaporation, and stream and groundwater outflow. If the expenses outweigh the income, the water budget is not balanced. In this case, water is removed from savings, i.e. water storage, if available. Reservoirs, snow, ice, soil moisture, and aquifers all serve as storage in a water budget. In dry regions, the water is critical for sustaining human activities. Understanding and managing the water budget is an ongoing political and social challenge.

Hydrologists create groundwater budgets within any designated area, but they are generally made for watershed (basin) boundaries, because groundwater and surface water are easier to account for within these boundaries. Water budgets can be created for state, county, or aquifer extent boundaries as well. The groundwater budget is an essential component of the hydrologic model; hydrologists use measured data with a conceptual workflow of the model to better understand the water system.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

11.3 Water Use and Distribution

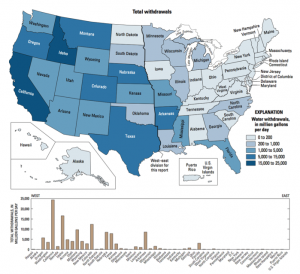

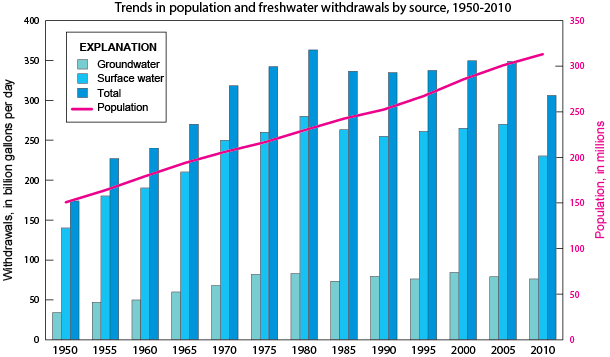

In the United States, 1,344 billion L (355 billion gallons) of ground and surface water are used each day, of which 288 billion L (76 billion gallons) are fresh groundwater. The state of California uses 16% of national groundwater [8].

Utah is the second driest state in the United States. Nevada, having a mean statewide precipitation of 31 cm (12.2 inches) per year, is the driest. Utah also has the second highest per capita rate of total domestic water use of 632.16 L (167 gallonsL per day per person [8]. With the combination of relatively high demand and limited quantity, Utah is at risk for water budget deficits.

11.3.1 Surface Water Distribution

Fresh water is a precious resource and should not be taken for granted, especially in dry climates. Surface water makes up only 1.2% of the fresh water available on the planet, and 69% of that surface water is trapped in ground ice and permafrost. Stream water accounts for only 0.006% of all freshwater and lakes contain only 0.26% of the world’s fresh water [9].

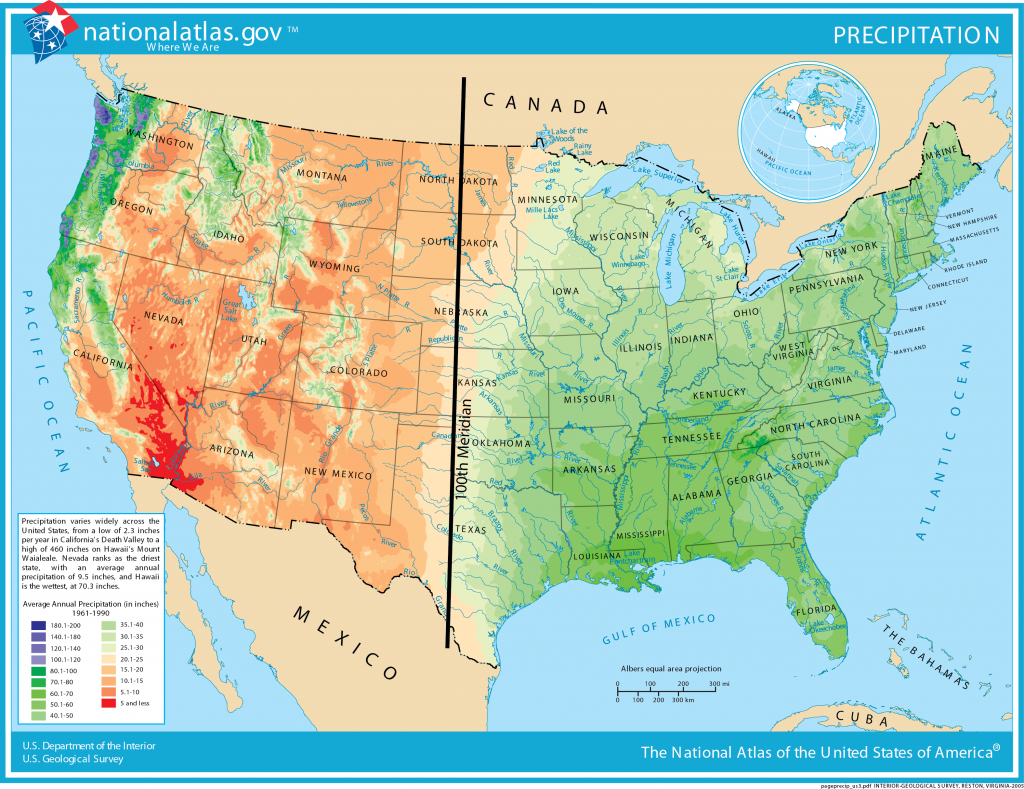

Global circulation patterns are the most important factor in distributing surface water through precipitation. Due to the Coriolis effect and the uneven heating of the Earth, air rises near the equator and near latitudes 60° north and south. Air sinks at the poles and latitudes 30° north and south (see Chapter 13). Land masses near rising air are more prone to humid and wet climates. Land masses near sinking air, which inhibits precipitation, are prone to dry conditions [10, 11]. Prevailing winds, ocean circulation patterns such as the Gulf Stream’s effects on eastern North America, rain shadows (the dry leeward sides of mountains), and even the proximity of bodies of water can affect local climate patterns. When this moist air collides with the nearby mountains causing it to rise and cool, the moisture may fall out as snow or rain on nearby areas in a phenomenon known as “lake-effect precipitation.” [12]

In the United States, the 100th meridian roughly marks the boundary between the humid and arid parts of the country. Growing crops west of the 100th meridian requires irrigation [13]. In the west, surface water is stored in reservoirs and mountain snowpacks [14], then strategically released through a system of canals during times of high water use.

Some of the driest parts of the western United States are in the Basin and Range Province. The Basin and Range has multiple mountain ranges that are oriented north to south. Most of the basin valleys in the Basin and Range are dry, receiving less than 30 cm (12 inches) of precipitation per year. However, some of the mountain ranges can receive more than 1.52 m (60 inches) of water as snow or snow-water-equivalent. The snow-water equivalent is the amount of water that would result if the snow were melted, as the snowpack is generally much thicker than the equivalent amount of water that it would produce [12].

11.3.2 Groundwater Distribution

| Water source | Water volume

(cubic miles) |

Fresh water (%) | Total water (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oceans, Seas, & Bays | 321,000,000 | -- | 96.5 |

| Ice caps, Glaciers, & Permanent Snow | 5,773,000 | 68.7 | 1.74 |

| Groundwater | 5,614,000 | -- | 1.69 |

| -- Fresh | 2,526,000 | 30.1 | 0.76 |

| -- Saline | 3,088,000 | -- | 0.93 |

| Soil Moisture | 3,959 | 0.05 | 0.001 |

| Ground Ice & Permafrost | 71,970 | 0.86 | 0.022 |

| Lakes | 42,320 | -- | 0.013 |

| -- Fresh | 21,830 | 0.26 | 0.007 |

| -- Saline | 20,490 | -- | 0.006 |

| Atmosphere | 3,095 | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| Swamp Water | 2,752 | 0.03 | 0.0008 |

| Rivers | 509 | 0.006 | 0.0002 |

| Biological Water | 269 | 0.003 | 0.0001 |

| Source: Igor Shiklomanov's chapter "World fresh water resources" in Peter H. Gleick (editor), 1993, Water in Crisis: A Guide to the World's Fresh Water Resources (Oxford University Press, New York)[zotpressInText item="{P7VGIQT4}" format="%num%" brackets="yes" separator="comma"] | |||

Groundwater makes up 30.1% of the fresh water on the planet, making it the most abundant reservoir of fresh water accessible to most humans. The majority of freshwater, 68.7%, is stored in glaciers and ice caps as ice [9]. As the glaciers and ice caps melt due to global warming, this fresh water is lost as it flows into the oceans.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

11.4 Water Law

Federal and state governments have put laws in place to ensure the fair and equitable use of water. In the United States, the states are tasked with creating a fair and legal system for sharing water.

11.4.1 Water Rights

Because of the limited supply of water, especially in the western United States, states disperse a system of legal water rights defined as a claim to a portion or all of a water source, such as a spring, stream, well, or lake. Federal law mandates that states control water rights, with the special exception of federally reserved water rights, such as those associated with national parks and Native American tribes, and navigation servitude that maintains navigable water bodies. Each state in the United States has a different way to disperse and manage water rights.

A person, entity, company, or organization, must have a water right to legally extract or use surface or groundwater in their state. Water rights in some western states are dictated by the concept of prior appropriation, or “first in time, first in right,” where the person with the oldest water right gets priority water use during times when there is not enough water to fulfill every water right.

The Colorado River and its tributaries pass through a desert region, including seven states (Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California), Native American reservations, and Mexico. As the western United States became more populated and while California was becoming a key agricultural producer, the states along the Colorado River realized that the river was important to sustaining life in the West.

To guarantee certain perceived water rights, these western states recognized that a water budget was necesary for the Colorado River Basin. Thus was enacted the Colorado River Compact in 1922 to ensure that each state got a fair share of the river water. The Compact granted each state a specific volume of water based on the total measured flow at the time. However, in 1922, the flow of the river was higher than its long-term average flow, consequently, more water was allocated to each state than is typically available in the river [16].

Over the next several decades, lawmakers have made many other agreements and modifications regarding the Colorado River Compact, including those agreements that brought about the Hoover Dam (formerly Boulder Dam), and Glen Canyon Dam, and a treaty between the American and Mexican governments. Collectively, the agreements are referred to as “The Law of the River" by the United States Bureau of Reclamation. Despite adjustments to the Colorado River Compact, many believe that the Colorado River is still over-allocated, as the Colorado River flow no longer reaches the Pacific Ocean, its original terminus (base level). Dams along the Colorado River have caused water to divert and evaporate, creating serious water budget concerns in the Colorado River Basin. Predicted drought associated with global warming is causing additional concerns about over-allocating the Colorado River flow in the future.

The Law of the River highlights the complex and prolonged nature of interstate water rights agreements, as well as the importance of water.

The Snake Valley straddles the border of Utah and Nevada with more of the irrigable land area lying on the Utah side of the border. In 1989, the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) submitted applications for water rights to pipe up to 191,189,707 cu m (155,000 ac-ft) of water per year (an acre-foot of water is one acre covered with water one foot deep) from Spring, Snake, Delamar, Dry Lake, and Cave valleys to southern Nevada, mostly for Las Vegas [17]. Nevada and Utah have attempted a comprehensive agreement, but negotiations have not yet been settled.

11.4.2 Water Quality and Protection

Two major federal laws that protect water quality in the United States are the Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act. The Clean Water Act, an amendment of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, protects navigable waters from dumping and point-source pollution. The Safe Drinking Water Act ensures that water that is provided by public water suppliers, like cities and towns, is safe to drink [18].

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Superfund program ensures the cleanup of hazardous contamination, and can be applied to situations of surface water and groundwater contamination. It is part of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980. Under this act, state governments and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency can use the superfund to pay for remediation of a contaminated site and then file a lawsuit against the polluter to recoup the costs. Or to avoid being sued, the polluter that caused the contamination may take direct action or provide funds to remediate the contamination.

Take this quiz to check your comprehension of this section.

11.5 Surface Water

Geologically, a stream is a body of flowing surface water confined to a channel. Terms such as river, creek and brook are social terms not used in geology. Streams erode and transport sediments, making them the most important agents of the earth’s surface, along with wave action (see Chapter 12) in eroding and transporting sediments. They create much of the surface topography and are an important water resource.

Several factors cause streams to erode and transport sediment, but the two main factors are stream-channel gradient and velocity. Stream-channel gradient is the slope of the stream usually expressed in meters per kilometer or feet per mile. A steeper channel gradient promotes erosion. When tectonic forces elevate a mountain, the stream gradient increases, causing the mountain stream to erode downward and deepen its channel eventually forming a valley. Stream-channel velocity is the speed at which channel water flows. Factors affecting channel velocity include channel gradient which decreases downstream, discharge and channel size which increase as tributaries coalesce, and channel roughness which decreases as sediment lining the channel walls decreases in size thus reducing friction. The combined effect of these factors is that channel velocity actually increases from mountain brooks to the mouth of the stream.

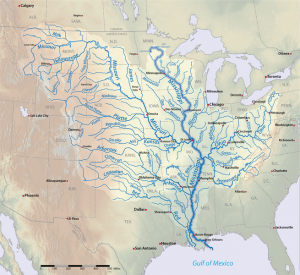

11.5.1 Discharge

Stream size is measured in terms of discharge, the volume of water flowing past a point in the stream over a defined time interval. Volume is commonly measured in cubic units (length x width x depth), shown as feet3 (ft3) or meter3 (m3). Therefore, the units of discharge are cubic feet per second (ft3/sec or cfs). Therefore, the units of discharge are cubic meters per second, (m³/s or cms, or cubic feet per second (ft³/sec or cfs). Stream discharge increases downstream. Smaller streams have less discharge than larger streams. For example, the Mississippi River is the largest river in North America, with an average flow of about 16,990.11 cms (600,000 cfs) [19]. For comparison, the average discharge of the Jordan River at Utah Lake is about 16.25 cms (574 cfs) [20] and for the annual discharge of the Amazon River, (the world’s largest river), annual discharge is about 175,565 cms (6,200,000 cfs) [21].

Discharge can be expressed by the following equation:

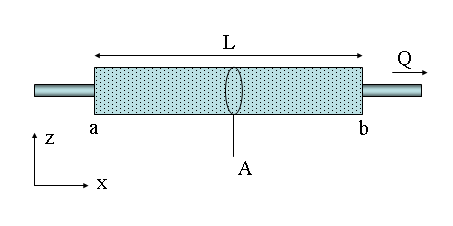

Q = V A

- Q = discharge cms (or ft3/sec),

- A = cross-sectional area of the stream channel [width times average depth] as m2 (or in2 or ft2),

- V = average channel velocity m/s (or ft/sec) [7]

At a given location along the stream, velocity varies with stream width, shape, and depth within the stream channel as well. When the stream channel narrows but discharge remains constant, the same volume of water must flows through a narrower space causing the velocity to increase, similar to putting a thumb over the end of a backyard water hose. In addition, during rain storms or heavy snow melt, runoff increases, which increases stream discharge and velocity.

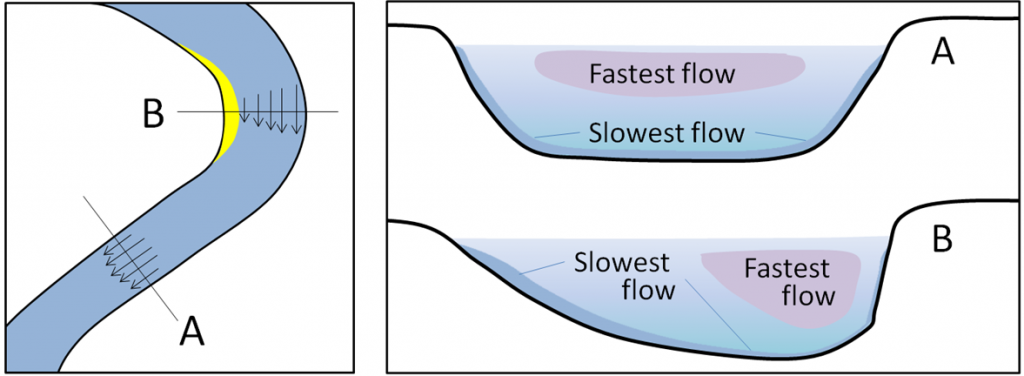

When the stream channel curves, the highest velocity will be on the outside of the bend. When the stream channel is straight and uniformly deep, the highest velocity is in the channel center at the top of the water where it is the farthest from frictional contact with the stream channel bottom and sides. In hydrology, the thalweg of a river is the line drawn that shows its natural progression and deepest channel, as is shown in the diagram.

11.5.2 Runoff vs. Infiltration

Factors that dictate whether water will infiltrate into the ground or run off over the land include the amount, type, and intensity of precipitation; the type and amount of vegetation cover; the slope of the land; the temperature and aspect of the land; preexisting conditions; and the type of soil in the infiltrated area. High- intensity rain will cause more runoff than the same amount of rain spread out over a longer duration. If the rain falls faster than the soil’s properties allow it to infiltrate, then the water that cannot infiltrate becomes runoff. Dense vegetation can increase infiltration, as the vegetative cover slows the water particle’s overland flow giving them more time to infiltrate. If a parcel of land has more direct solar radiation or higher seasonal temperatures, there will be less infiltration and runoff, as evapotranspiration rates will be higher. As the land’s slope increases, so does runoff, because the water is more inclined to move downslope than infiltrate into the ground. Extreme examples are a basin and a cliff, where water infiltrates much quicker into a basin than a cliff that has the same soil properties. Because saturated soil does not have the capacity to take more water, runoff is generally greater over saturated soil. Clay-rich soil cannot accept infiltration as quickly as gravel-rich soil.

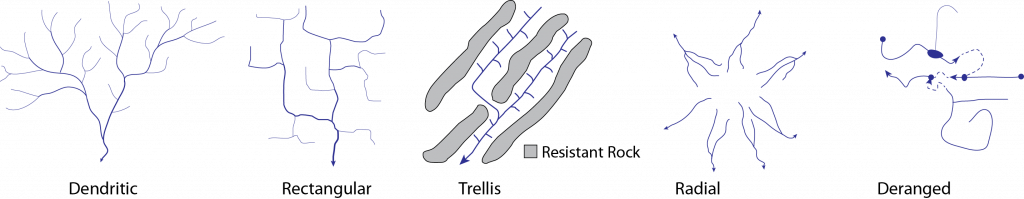

11.5.3 Drainage Patterns

The pattern of tributaries within a region is called drainage pattern. They depend largely on the type of rock beneath, and on structures within that rock (such as folds and faults). The main types of drainage patterns are dendritic, trellis, rectangular, radial, and deranged. Dendritic patterns are the most common and develop in areas where the underlying rock or sediments are uniform in character, mostly flat lying, and can be eroded equally easily in all directions. Examples are alluvial sediments or flat lying sedimentary rocks. Trellis patterns typically develop where sedimentary rocks have been folded or tilted and then eroded to varying degrees depending on their strength. The Appalachian Mountains in eastern United States have many good examples of trellis drainage. Rectangular patterns develop in areas that have very little topography and a system of bedding planes, joints, or faults that form a rectangular network. A radial pattern forms when streams flow away from a central high point such as a mountain top or volcano, with the individual streams typically having dendritic drainage patterns. In places with extensive limestone deposits, streams can disappear into the groundwater via caves and subterranean drainage and this creates a deranged pattern [4].

11.5.4 Fluvial Processes

Fluvial processes dictate how a stream behaves and include factors controlling fluvial sediment production, transport, and deposition. Fluvial processes include velocity, slope and gradient, erosion, transportation, deposition, stream equilibrium, and base level.

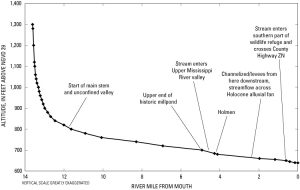

Streams can be divided into three main zones: the many smaller tributaries in the source area, the main trunk stream in the floodplain and the distributaries at the mouth of the stream. Major stream systems like the Mississippi are composed of many source areas, many tributaries and trunk streams, all coalescing into the one main stream draining the region. The zones of a stream are defined as 1) the zone of sediment production (erosion), 2) the zone of transport, and 3) the zone of deposition. The zone of sediment production is located in the headwaters of the stream. In the zone of sediment transport, there is a general balance between erosion of the finer sediment in its channel and transport of sediment across the floodplain. Streams eventually flow into the ocean or end in quiet water with a delta which is a zone of sediment deposition located at the mouth of a stream [6]. The longitudinal profile of a stream is a plot of the elevation of the stream channel at all points along its course and illustrates the location of the three zones [22]

Zone of Sediment Production

The zone of sediment production is located in the headwaters of a stream where rills and gullies erode sediment and contribute to larger tributary streams. These tributaries carry sediment and water further downstream to the main trunk of the stream. Tributaries at the headwaters have the steepest gradient; erosion there produces considerable sediment carried b the stream. Headwater streams tend to be narrow and straight with small or non-existent floodplains adjacent to the channel. Since the zone of sediment production is generally the steepest part of the stream, headwaters are generally located in relatively high elevations. The Rocky Mountains of Wyoming and Colorado west of the Continental Divide contain much of the headwaters for the Colorado River which then flows from Colorado through Utah and Arizona to Mexico. Headwaters of the Mississippi river system lie east of the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains and west of the Appalachian Divide.

Zone of Sediment TransPORT

Streams transport sediment great distances from the headwaters to the ocean, the ultimate depositional basins. Sediment transportation is directly related to stream gradient and velocity. Faster and steeper streams can transport larger sediment grains. When velocity slows down, larger sediments settle to the channel bottom. When the velocity increases, those larger sediments are entrained and move again.

Transported sediments are grouped into bedload, suspended load, and dissolved load as illustrated in the above image. Sediments moved along the channel bottom are the bedload that typically consists of the largest and densest particles. Bedload is moved by saltation (bouncing) and traction (being pushed or rolled along by the force of the flow). Smaller particles are picked up by flowing water and carried in suspension as suspended load. The particle size that is carried in suspended and bedload depends on the flow velocity of the stream. Dissolved load in a stream is the total of the ions in solution from chemical weathering, including such common ions such as bicarbonate (-HCO3-), calcium (Ca+2), chloride (Cl-1), potassium (K+1), and sodium (Na+1). The amounts of these ions are not affected by flow velocity.

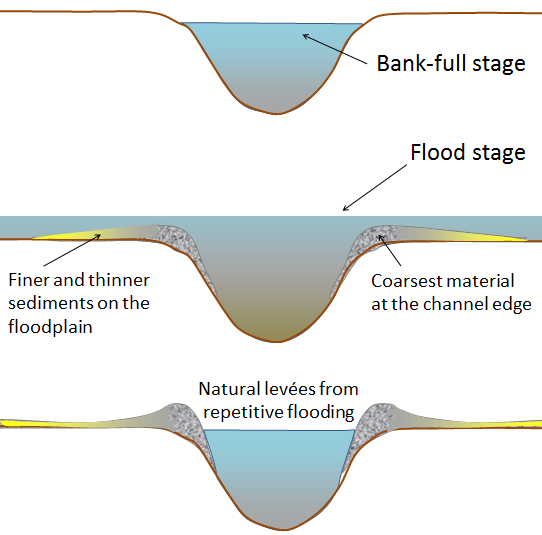

A floodplain is the flat area of land adjacent to a stream channel inundated with flood water on a regular basis. Stream flooding is a natural process that adds sediment to floodplains. A stream typically reaches its greatest velocity when it is close to flooding, known as the bankfull stage. As soon as the flooding stream overtops its banks and flows onto its floodplain, the velocity decreases. Sediment that was being carried by the swiftly moving water is deposited at the edge of the channel, forming a low ridge or natural levée. In addition, sediments are added to the floodplain during this flooding process contributing to fertile soils [4].

Zone of SEDIMENT Deposition

Deposition occurs when bedload and suspended load come to rest on the bottom of the stream channel, lake, or ocean due to decrease in stream gradient and reduction in velocity. While both deposition and erosion occur in the zone of transport such as on point bars and cut banks, ultimate deposition where the stream reaches a lake or ocean. Landforms called deltas form where the stream enters quiet water composed of the finest sediment such as fine sand, silt, and clay.

Equilibrium and Base Level

All three stream zones are present in the typical longitudinal profile of a stream which plots the elevation of the channel at all points along its course (see figure). All streams have a long profile. The long profile shows the stream gradient from headwater to mouth. All streams attempt to achieve an energetic balance among erosion, transport, gradient, velocity, discharge, and channel characteristics along the stream’s profile. This balance is called equilibrium, a state called grade.

Another factor influencing equilibrium is base level, the elevation of the stream's mouth representing the lowest level to which a stream can erode. The ultimate base level is, of course, sea-level. A lake or reservoir may also represent base level for a stream entering it. The Great Basin of western Utah, Nevada, and parts of some surrounding states contains no outlets to the sea and provides internal base levels for streams within it. Base level for a stream entering the ocean changes if sea-level rises or falls. Base level also changes if a natural or human-made dam is added along a stream's profile. When base level is lowered, a stream will cut down and deepen its channel. When base level rises, deposition increases as the stream adjusts attempting to establish a new state of equilibrium. A stream that has approximately achieved equilibrium is called a graded stream.

11.5.5 Fluvial Landforms

Stream landforms are the land features formed on the surface by either erosion or deposition. The stream-related landforms described here are primarily related to channel types.

Channel Types

Stream channels can be straight, braided, meandering, or entrenched. The gradient, sediment load, discharge, and location of base level all influence channel type. Straight channels are relatively straight, located near the headwaters, have steep gradients, low discharge, and narrow V-shaped valleys. Examples of these are located in mountainous areas.

Braided streams have multiple channels splitting and recombining around numerous mid-channel bars. These are found in floodplains with low gradients in areas with near sources of coarse sediment such as trunk streams draining mountains or in front of glaciers.

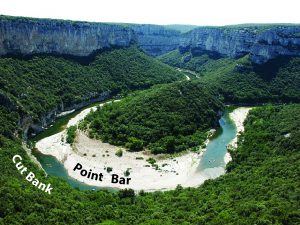

Meandering streams have a single channel that curves back and forth like a snake within its floodplain where it emerges from its headwaters into the zone of transport. Meandering streams are dynamic creating a wide floodplain by eroding and extending meander loops side-to-side. The highest velocity water is located on the outside of a meander bend. Erosion of the outside of the curve creates a feature called a cut bank and the meander extends its loop wider by this erosion.

The thalweg of the stream is the deepest part of the stream channel. In the straight parts of the channel, the thalweg and highest velocity are in the center of the channel. But at the bend of a meandering stream, the thalweg shifts toward the cut bank. Opposite the cutbank on the inside bend of the channel is the lowest stream velocity and is an area of deposition called a point bar.

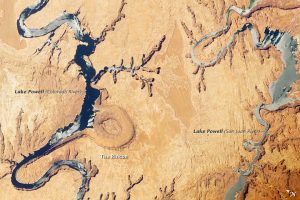

In areas of tectonic uplift such as on the Colorado Plateau, meandering streams that once flowed on the plateau surface have become entrenched or incised as uplift occurred and the stream cut its meandering channel down into bedrock. Over the past several million years, the Colorado River and its tributaries have incised into the flat lying rocks of the plateau by hundreds, even thousands of feet creating deep canyons including the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

Many fluvial landforms occur on a floodplain associated with a meandering stream. Meander activity and regular flooding contribute to widening the floodplain by eroding adjacent uplands. The stream channels are confined by natural levees that have been built up over many years of regular flooding. Natural levees can isolate and direct flow from tributary channels on the floodplain from immediately reaching the main channel. These isolated streams are called yazoo streams and flow parallel to the main trunk stream until there is an opening in the levee to allow for a belated confluence.

To limit flooding, humans build artificial levees on flood plains. Sediment that breaches the levees during flood stage is called crevasse splays and delivers silt and clay onto the floodplain. These deposits are rich in nutrients and often make good farm land. When floodwaters crest over human-made levees, the levees quickly erode with potentially catastrophic impacts. Because of the good soils, farmers regularly return after floods and rebuild year after year.

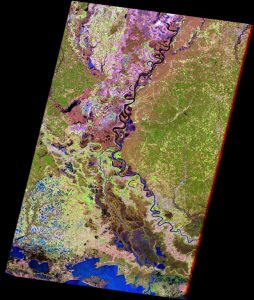

Through erosion on the outsides of the meanders and deposition on the insides, the channels of meandering streams move back and forth across their floodplain over time. On very broad floodplains with very low gradients, the meander bends can become so extreme that they cut across themselves at a narrow neck (see figure) called a cutoff. The former channel becomes isolated and forms an oxbow lake seen on the right of the figure. Eventually the oxbow lake fills in with sediment and becomes a wetland and eventually a meander scar. Stream meanders can migrate and form oxbow lakes in a relatively short amount of time. Where stream channels form geographic and political boundaries, this shifting of channels can cause conflicts.

Alluvial fans are a depositional landform created where streams emerge from mountain canyons into a valley. The channel that had been confined by the canyon walls is no longer confined, slows down and spreads out, dropping its bedload of all sizes, forming a delta in the air of the valley. As distributary channels fill with sediment, the stream is diverted laterally, and the alluvial fan develops into a cone shaped landform with distributaries radiating from the canyon mouth. Alluvial fans are common in the dry climates of the West where ephemeral streams emerge from canyons in the ranges of the Basin and Range.

A delta is formedwhen a stream reaches a quieter body of water such as a lake or the ocean and the bedload and suspended load is deposited. If wave erosion from the water body is greater than deposition from the river, a delta will not form. The largest and most famous delta in the United States is the Mississippi River delta formed where the Mississippi River flows into the Gulf of Mexico. The Mississippi River drainage basin is the largest in North America, draining 41% of the contiguous United States [24]. Because of the large drainage area, the river carries a large amount of sediment. The Mississippi River is a major shipping route and human engineering has ensured that the channel has been artificially straightened and remains fixed within the floodplain. The river is now 229 km shorter than it was before humans began engineering it [24]. Because of these restraints, the delta is now focused on one trunk channel and has created a “bird’s foot” pattern. The two NASA images below of the delta show how the shoreline has retreated and land was inundated with water while deposition of sediment was focused at end of the distributaries. These images have changed over a 25 year period from 1976 to 2001. These are stark changes illustrating sea-level rise and land subsidence from the compaction of peat due to the lack of sediment resupply [25].

The formation of the Mississippi River delta started about 7500 years ago when postglacial sea level stopped rising. In the past 7000 years, prior to anthropogenic modifications, the Mississippi River delta formed several sequential lobes. The river abandoned each lobe for a more preferred route to the Gulf of Mexico. These delta lobes were reworked by the ocean waves of the Gulf of Mexico [26]. After each lobe was abandoned by the river, isostatic depression and compaction of the sediments caused basin subsidence and the land to sink.