2

Inclusive Language

How we communicate as caregivers and as Nursing Educators has a significant impact on both our students and our patients. Culturally competent care includes being self-aware of the ways in which we talk to – and talk about – our patients. Our communication patterns demonstrate our commitment to patient advocacy, or contribute to potential health disparities, and poor outcomes. But we are more than just nursing role models to our students: we have the power to create learning environments that are inclusive, respectful, affirming, and empowering.

We as Nurse Educators are expanding our understanding of diversity itself. We are learning that language biases are present in healthcare and problematic in a myriad of ways. Non-inclusive terminology can reveal negative attitudes in caregivers and may result in bad experiences for patients, which in turn can increase health disparities for vulnerable populations. Those negative experiences and perceptions can keep people from receiving the healthcare they need (Sommer, et al., 2019). Processes to counter language biases include: self-assessments (such as implicit bias assessments), terminology education, interventions and advocacy when biases are identified, and evaluating the educational materials that may contribute to unintended biases (Sommer, et al., 2019). These strategies not only help our patients, but also create a conscientious environment that demonstrates to students that our learning environment is welcoming and equitable.

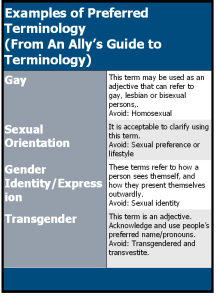

Our language is evolving, even as we speak it. The first step in becoming an inclusive communicator is to learn about the terminology that helps describe the diversity around us. Several resources exist which provide basic definitions that can help us, such as the Inclusive Language Guide by the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) (available at https://www.ohsu.edu/sites/default/files/2021-03/OHSU%20Inclusive%20Language%20Guide_031521.pdf), which describes itself as an “identity affirming” and “evolving tool” that provides a wealth of information about the descriptive language that can be used related to race, ethnicity, immigration status, gender, sexual orientation, and ability (including physical, mental and chronological attributes) (2021). The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) offer guidance as well, such as in these Clinican Resources (available at https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/transforming-health/health-care-providers/collecting-sexual-orientation.html) that can help caregivers gather patient health information in a sensitive and respectful way (2021).

The electronic health records are trying to catch up to the needs of our diverse patient population, but in the meantime, the use of nursing notes and consistent interprofessional communication can help minimize errors in patient identification. Addressing the limitations and potential problems facing healthcare providers in an honest and open way with nursing students can help them be on alert for issues even before they arise. Exposure to diversity in the academic setting can help create a safe environment to ask questions and learn. Nursing students who are trained with empathy, compassion, nonjudgmental attitudes and an advocating spirit will likely take those qualities into their careers.

A significant challenge that may arise with multi-generational students and educators is the evolution of acceptable terminology. Older nurses and students may have been raised with an array of terms to describe race, gender, (dis)abilities, etc., and may not even be aware that those antiquated terms are no longer appropriate in our society. Encouraging exploration of language and diversity, creating a safe place to self-assess and grow, and providing resources and guidance are essential elements to helping people blossom together – and that promotes equity and inclusion in both academic and healthcare spaces.

A good strategy is to start with using people-first terminology. That is, identifying a person by their personhood first, before adding any additional information to their description (Likis, 2021). For example, saying that your patient is a person with a mental illness, rather than a mentally ill person. This seemingly minor detail speaks volumes about the idea that the person is the most important part of the equation – not their mental illness (or other “identifying” characteristic). An ongoing consideration is that terminology is part of a rapidly changing language-landscape, and it is possible that what is considered acceptable today might be regarded as discriminatory or problematic tomorrow. Keeping informed and being willing to ask with humility and genuine altruism is the best way to navigate communication strategies successfully.

When discussing gender and the use of pronouns, one way to convey acceptance is to introduce yourself with your pronouns, and then be sure to develop a consistent habit of asking and respecting other people’s pronouns and identity descriptors. For example, starting the conversation with, “Hello, my name is X, and I use she/her pronouns. May I ask your name and your preferred pronouns?” Simple statements like this send a clear message of acceptance and inclusion. When mistakes are made – as mistakes are inevitable – it is essential to self-correct quickly and without excessive attention being drawn to the mistake. The goal is to modify and move on, and not make the other person feel any more uncomfortable during the interaction. A genuine “I am sorry” is sufficient, and then a conscientious effort to utilize correct terminology going forward. As we explore, learn about and share DEI knowledge, our use of inclusive language becomes a bridge that can help us connect better with our patients and our students.

The OSHU guide and the CDC articles provide terminology recommendations to improve the inclusivity and respect of the language used in healthcare, and those recommendations can be used to improve nursing education (for examples of recommended terminology, see Table 1). The best of these recommendations is to utilize the most effective communication strategy known: ask the patient what their preferences are when you address them.